IT IS widely recognized that the worldwide prevalence of allergic diseases has been steadily increasing, especially in industrialized countries(1). Major allergic disease phenotypes include rhinitis, asthma, food allergy, and atopic eczema that all derive from hyper-reactive allergic immune responses. Pollutants and chemicals have been suggested to contribute to allergic sensitization. In addition, improved hygiene with fewer microbes in food and the environment of modern society may also contribute to an increased prevalence of allergic disease. The proposed link between a reduced microbial exposure of the immune system and allergic disease is known as the “hygiene hypothesis”(10).

Giving specific probiotic strains and supplementation of probiotics to mothers and infants seems to be the most efficient way to provide help to infants’ immune development

Considering that our immune system has co-evolved with microbes for millions of years, it was been proposed that the sudden decrease in microbial richness of the environment and in food has created a challenge for our immune systems, resulting in an increased prevalence of allergic disease. As we are starting to recognize the rationale behind the increasing prevalence of allergies, it has been suggested that fortification of food and dietary supplements with beneficial microbes could offer a solution, by compensating for a reduced microbial diversity of the modern life. Since the beginning of the 21st century, the number of scientific publications on the influence of microbiota on our immune system and health has been increasing exponentially, at the same time clinical data on the efficacy of probiotics on allergic disease risk has emerged. This review will discuss the current evidence on probiotic efficacy and how probiotics, especially L. rhamnosus HN001 can have a role in reducing the prevalence of childhood allergy, including allergic rhinitis and eczema.

Probiotics

Probiotics have been defined as: “Live microorganisms which when administered in adequate amounts confer a health benefit on the host”. This definition was coined by a FAO/WHO work group in 2002(15). A probiotic microorganism may belong to any genus or species, as long as it fulfills the requirements for the definition. However, most commonly used probiotics in food industry belong to the genera Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium – both of which are important for early life microbiota. The exact mechanisms by which probiotics exert their effects have not yet been fully elucidated, but are likely to be multifactorial. It is assumed that probiotic benefits result directly or indirectly from modulation of the composition and/or activity of the host’s microbiota and/or the stimulation of the immune system(2).

Microbiota is the key driver of immune system development

The microbiota, i.e. all the microbes that colonize the gastrointestinal tract, has an important role in the development of a healthy immunity. Sterile mice lacking microbiota have under-developed immune organs and cells, compared to conventional mice, and thus it was concluded that immune system essentially needs signals from microbiota for proper function and for the establishment of tolerance to allergens(3). The immune system is especially sensitive to these microbe derived signals over a period from birth up to 2 years of age. This period of early childhood is also a critical time where allergic disease often develop in the absence of proper stimuli(4). It is well established that during natural birth, the child is exposed to vaginal microbes that starts the microbial colonization of the intestine, however, recent evidence indicate that already before birth, the fetus would be exposed to microbes from mother that could establish a starter microbiota in utero(11). These findings further underline the importance of the maternal nutrition and microbiota for infant’s health during pregnancy. In addition, it has been demonstrated that microbes translocate within immune cells from intestine to breast milk that adds another element on transfer of microbiota from mother to infant, if breastfeeding is successful. The maternal microbiota may also impact on the fetus immune system by affecting the profile of maternal cytokines and other immune signaling molecules that are transported in the cord blood. After birth, maternal cytokines and antibodies can also be transferred to the infant via breast milk(9). Thus mothers use various means to provide information about the environmental microbes to their offspring.

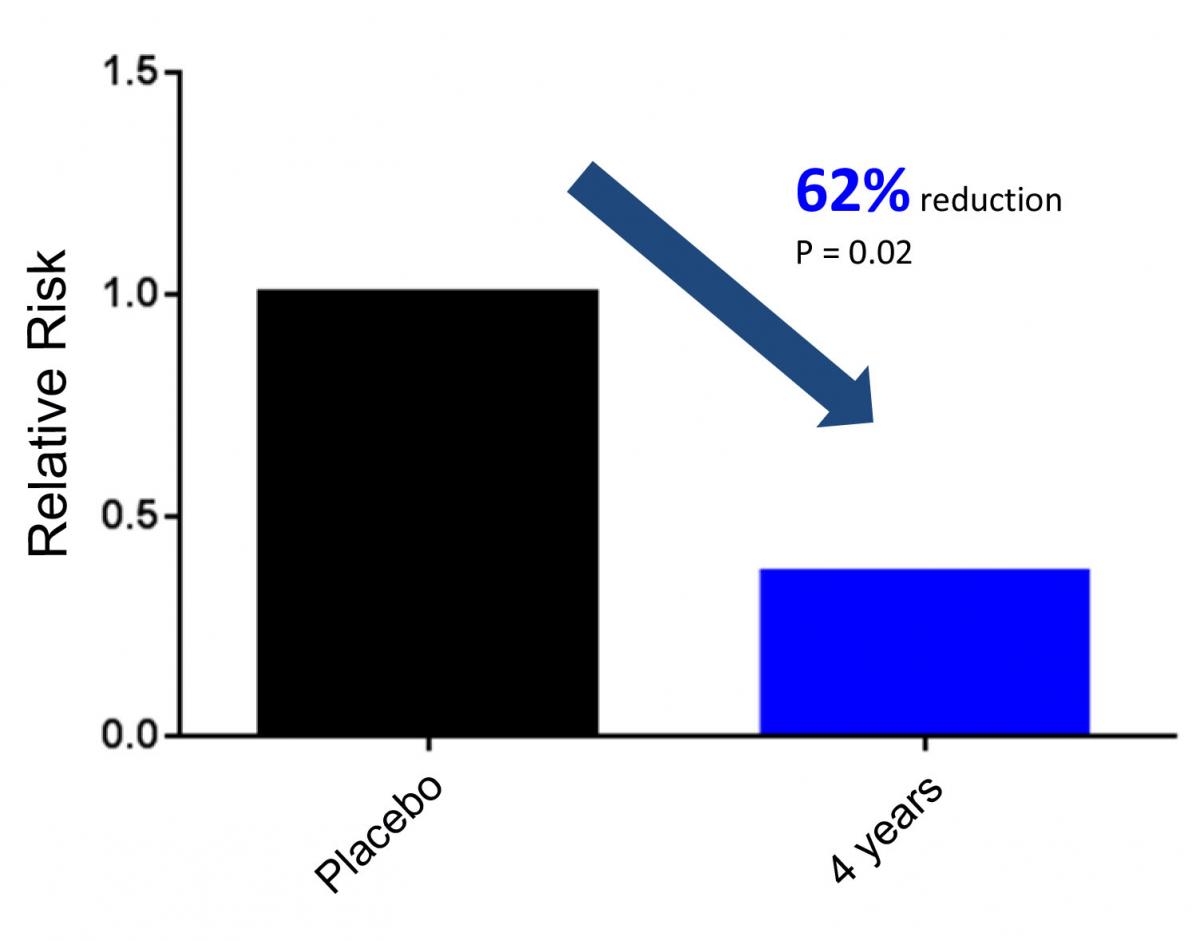

Relative risk of children developing rhinoconjunctivitis (rhinitis and conjunctivitis) at 4 years of age. Children were treated with either probiotics (HN001) or placebo from birth up to the age of 2 years. Only 5.9% of children given probiotics experienced symptoms in the past year, while 15.4% of children in the placebo group had symptoms of rhinoconjunctivitis in the past year. Results adapted from Wickens et al (13).

Clinical evidence on the efficacy of probiotics

The number of clinical studies looking at the efficacy of probiotics against allergic disease is still relatively small (in order of tens of studies) and some have resulted in positive and some in neutral results(7). For treating already established eczema or atopic dermatitis the evidence is not so strong, despite some positive results(6). The most convincing evidence has been found on preventing eczema and atopic eczema(6). The effect of several different probiotic strains is so far inconclusive. But if there is a clear link between microbiota, immunity and allergies, why would some probiotics be ineffective? There are at least two important factors to consider: (1) strain specificity and (2) the period over which the supplementation takes place. It is generally accepted that the immunological effects of probiotics are strain specific(5), and thus some probiotics work better than the others, it is just not known if a particular probiotic strain is effective without testing in a clinical trial. The other factor to consider in preventive allergy studies is if the supplementation is given throughout the critical period (pre-natal to 2 years of age), when the immune system develops, or if supplementation is given under a less critical period. Interestingly, if we consider the eczema studies, 50 % (5 out of 10) of the probiotic studies were successful if supplementation was given to mothers and their babies, whereas if supplementation was given only to infant or to mother, 25% (1 out of 4) and 0% (0 out of 1) were successful, respectively. Thus the key to achieve protection against eczema seems to be in specific strains and in supplementing the pregnant mother and the infant throughout the time of immune system development.

Probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus HN001

One of the best studies on probiotic efficacy against allergic diseases was conducted in New Zealand where mother-baby pairs were recruited to a double-blind clinical intervention trial with three parallel supplementation groups (Lactobacillus rhamnosus HN001, Bifidobacterium lactis HN019 and placebo)(13). The mothers consumed the investigational products from 35 weeks gestation until 6 months if breastfeeding and the new-born children consumed the same investigational product some days after birth until 2 years of age. The probiotic dose was 6x109 colony forming units per day for HN001 that was administered in capsules to mothers and as powder, powder diluted to milk, or sprinkled on top of the food to infants. The prevalence of eczema, asthma, rhinitis and allergic sensitization were determined at the age of 2, 4, and 6 years(12, 13, 14).

By using clinical diagnostic criteria it was found that HN001 reduced the cumulative prevalence of eczema in children at 2 years and the effect lasted up to 6 years of age. Furthermore, the children in HN001 group had significant reduction in the cumulative prevalence of skin prick test positivity against common allergens compared with children taking placebo at 6 years of age. At 4 years of age, the prevalence of rhinitis was significantly lower in the group that had received L. rhamnosus HN001, compared to placebo (Figure 1). These results indicate that HN001 assists in the development of a healthy immune system, resulting in lower risk of allergic disease. Interestingly, HN019 had no significant effect in this trial suggesting that probiotic efficacy was strain specific. However, in a follow-up study, looking at the association between probiotic supplementation and genetic susceptibility to eczema and atopy, it was found that HN019 could potentially be protective in children having certain genetic risk alleles(8). For the HN001 supplementation group the results were even more convincing as it was found to be protective against several risk alleles that could explain its better clinical efficacy over HN019 against eczema and atopy(8).

Potential immunological mechanisms of HN001 were investigated by Prescott and colleagues(9) who analyzed a cord blood and breast milk from cohort (n=105) of Wickens study mother-baby pairs. It was reported that infants in HN001 group had higher levels of anti-allergic immunological biomarkers in their cord blood and antibody levels in breast milk of mothers taking HN001 tended to be higher than in placebo group, suggesting again the importance of maternal nutrition for infant health. Although exact mechanisms of action of HN001 remain elusive, these immunological observations support the role of microbiota and immunomodulation in mediating clinical benefits on eczema and allergic sensitization by HN001.

Application of L. rhamnosus HN001 in dietary supplements and food

Lactobacillus rhamnosus HN001 can be administrated through a variety of delivery formats, including capsules, sachets and other dietary supplements. This strain can also be included in fresh and fermented dairy products and many other types of food. It is recommended that this probiotic strain is consumed at 6Billion (6E+09) live cells per day, which is in line with the dose used in Wickens et al(12, 13, 14).

Conclusions

The evidence of an amazing microbial and immunological symbiosis between mothers and their babies are accumulating, demonstrating a delicate balance between microbiota and immunity during fetal and infant life. Probiotics are promising functional foods for helping the development of children’s microbiota and immune system, however, mechanisms contributing to beneficial effects are not yet clear. However, in the light of current studies, giving specific probiotic strains and supplementation of probiotics to mothers and infants seems to be the most efficient way to provide help to infants’ immune development and, as in the case of L. rhamnosus HN001, potentially decrease the risk of eczema and allergic rhinitis. It is anticipated that the use of this probiotic strain in food and supplements will help in reducing the prevalence of allergic disease in childhood and beyond.

*Markus J Lehtinen is R&D Manager and Anders Henriksson is Principal Application Specialist at DuPont Nutrition & Health

References

- Akinbami, L. J., J. E. Moorman and X. Liu (2011). "Asthma prevalence, health care use, and mortality: United States, 2005-2009." Natl Health Stat Report(32): 1-14.

- Bermudez-Brito, M., J. Plaza-Diaz, S. Muñoz-Quezada, C. Gómez-Llorente and A. Gil (2012). "Probiotic mechanisms of action." Ann Nutr Metab 61(2): 160-174.

- Cukrowska, B., H. Kozáková, Z. Rehákova, J. Sinkora and H. Tlaskalová-Hogenová (2001). "Specific antibody and immunoglobulin responses after intestinal colonization of germ-free piglets with non-pathogenic Escherichia coli O86." Immunobiology 204(4): 425-433.

- Hawrylowicz, C. and K. Ryanna (2010). "Asthma and allergy: the early beginnings." Nat Med 16(3): 274-275.

- Hill, C., F. Guarner, G. Reid, G. R. Gibson, D. J. Merenstein, B. Pot, L. Morelli, R. B. Canani, H. J. Flint, S. Salminen, P. C. Calder and M. E. Sanders (2014). "Expert consensus document. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic." Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 11(8): 506-514.

- Ismail, I. H., P. V. Licciardi and M. L. Tang (2013). "Probiotic effects in allergic disease." J Paediatr Child Health 49(9): 709-715.

- Kim, H. J., H. Y. Kim, S. Y. Lee, J. H. Seo, E. Lee and S. J. Hong (2013). "Clinical efficacy and mechanism of probiotics in allergic diseases." Korean J Pediatr 56(9): 369-376.

- Morgan, A. R., D. Y. Han, K. Wickens, C. Barthow, E. A. Mitchell, T. V. Stanley, J. Dekker, J. Crane and L. R. Ferguson (2014). "Differential modification of genetic susceptibility to childhood eczema by two probiotics." Clin Exp Allergy 44(10): 1255-1265.

- Prescott, S. L., K. Wickens, L. Westcott, W. Jung, H. Currie, P. N. Black, T. Stanley, E. A. Mitchell, P. Fitzharris, R. Siebers, L. Wu and J. Crane. (2008) "Supplementation with Lactobacillus rhamnosus or Bifidobacterium lactis probiotics in pregnancy increases cord blood interferon- γ and breast milk transforming growth factor- β and immunoglobin A detection." Clin Exp Allergy, 38, 1606–1614

- Strachan, D. P. (2000). "Family size, infection and atopy: the first decade of the "hygiene hypothesis"." Thorax 55 Suppl 1: S2-10.

- Wassenaar, T. M. and P. Panigrahi (2014). "Is a foetus developing in a sterile environment?" Lett Appl Microbiol 59(6): 572-579.

- Wickens, K., P. Black, T. V. Stanley, E. Mitchell, C. Barthow, P. Fitzharris, G. Purdie and J. Crane (2012). "A protective effect of Lactobacillus rhamnosus HN001 against eczema in the first 2 years of life persists to age 4 years." Clin Exp Allergy 42(7): 1071-1079.

- Wickens, K., P. N. Black, T. V. Stanley, E. Mitchell, P. Fitzharris, G. W. Tannock, G. Purdie and J. Crane (2008). "A differential effect of 2 probiotics in the prevention of eczema and atopy: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial." J Allergy Clin Immunol 122(4): 788-794.

- Wickens, K., T. V. Stanley, E. A. Mitchell, C. Barthow, P. Fitzharris, G. Purdie, R. Siebers, P. N. Black and J. Crane (2013). "Early supplementation with Lactobacillus rhamnosus HN001 reduces eczema prevalence to 6 years: does it also reduce atopic sensitization?" Clin Exp Allergy 43(9): 1048-1057.

iConnectHub

iConnectHub

Login/Register

Login/Register Supplier Login

Supplier Login