To detect head trauma immediately, a team of researchers has developed a polymer-based material that changes colors depending on how hard it is hit. The goal is to someday incorporate this material into protective headgear, providing an obvious indication of injury. The team described their approach in one of more than 9,000 presentations at the 250th National Meeting & Exposition of the American Chemical Society (ACS), the world's largest scientific society.

Recent research and media accounts have indicated that soldiers and professional athletes may suffer long-term complications -- such as memory loss, headaches and dementia -- stemming from past head trauma. There is no easy way to tell if someone has just sustained a brain injury, so soldiers and athletes may unknowingly continue to do the very activity that caused the damage and potentially cause more harm. But a force-responsive, color-changing patch could prevent additional injury, says Shu Yang, Ph.D. "If the force was large enough, and you could easily tell that, then you could immediately seek medical attention," she explains.

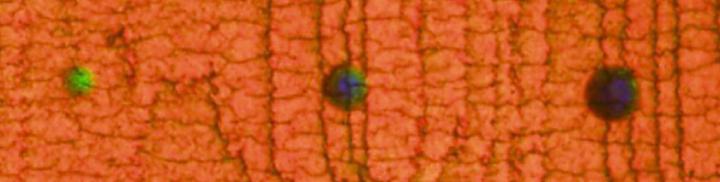

Microscopy images of the photonic crystals after nano-indentation at 30 mN (left), 60 mN (middle) and 90 mN (right) are shown. (Image credit: Yang lab)

Yang's team at the University of Pennsylvania used holographic lithography (HL) to create photonic crystals with carefully designed structures to give them a particular color, just like opals. Deforming the crystals with an applied force changes their internal structures, and thus the crystal's color. The material does not require power to detect forces and is lightweight, thus offering an attractive way for medical personnel to identify a damaging force on-site without the use of expensive tools. However, making these crystals is an expensive process that isn't suitable for the mass production, she says.

So the team turned to self-assembly and polymer-based materials that are cheaper to produce over a large area than the earlier HL method. Younghyun Cho, Ph.D., a postdoctoral fellow in Yang's lab, will describe the team's development, which could offer a path to commercialization.

The first step was to mold the polymer into a structure that worked just like the specialized photonic crystals. To make a mold, the researchers mixed up silica particles of various sizes and allowed them to self-assemble into crystals with the desired pattern. They heated the polymer, which infiltrated the mold, allowed it to solidify and then removed the silica mold, leaving behind the inversed polymer crystals.

The researchers then applied varying amounts of force to the polymer crystal and recorded the color change. The results were encouraging. "We were able to change the color consistently with certain forces," Yang says. For example, applying a 30 mN force -- approximately the force of a sedan moving at 80 miles per hour crashing into a brick wall -- caused the crystal to change from red to green. A force of 90 mN -- the equivalent of a speeding truck hitting that same wall -- turned the polymer purple, Cho adds. "This force is right in the range of a blast injury or a concussion," Yang says.

In future studies, Yang plans to develop materials that can indicate how quickly a force is applied, which affects how damaging a particular trauma is on the brain.

The American Chemical Society is a nonprofit organization chartered by the U.S. Congress. With more than 158,000 members, ACS is the world's largest scientific society and a global leader in providing access to chemistry-related research through its multiple databases, peer-reviewed journals and scientific conferences.

iConnectHub

iConnectHub

Login/Register

Login/Register Supplier Login

Supplier Login