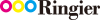

Machining operations focus on producing accurate parts at the lowest cost, thereby maximising profitability. The traditional way to lower machining costs is to accelerate production rates with more aggressive machining parameters, usually focusing on faster cutting speeds. That approach, however, does not recognise significant cost factors including the expense of scrapped parts and production downtime. A strategy that takes an overall process view of production economics provides the best balance of productivity and manufacturing costs, with all cost factors included.

Cost control

Some elements of manufacturing costs are essentially beyond a manufacturer’s control. For example, workpiece material type and cost are dictated by the end use of the machined component. It is not possible to save money by substituting gray cast iron for Inconel® in a turbine engine. Similarly, a facility’s investment in machine tools, their maintenance, and the power to run them is basically a fixed cost, usually involving ongoing payments on equipment loans. Labour costs are somewhat more flexible, but are effectively fixed for at least the short term. All these costs and the tooling costs must be offset with revenue from the sale of machined components. Raising production rate — the speed at which workpieces are converted into finished products — can offset fixed costs.

Faster is not necessarily better

Machining process elements that manufacturers can control include the parameters at which cutting tools are employed. Different tools, techniques, and strategies will affect production rates. Further, many shops believe that simply increasing cutting speeds will produce more parts per period of time and thereby reduce manufacturing costs.

The situation is more complex than that. Higher cutting speeds have a price. In general, the faster an operation is run, the less stable it becomes. Stresses, including increased cutting forces and heat generation, affect the tool and workpiece alike. Tool wear is faster and less predictable. A tool may break and scar the workpiece, and tool wear or vibration can cause part dimensions to vary and/or surface finish to decline. The result is ruined workpieces, the cost of which must be subtracted from profits. Depending on the value of the workpiece material and the final application of the component — for example, a costly superalloy intended for a complex aerospace component — scrapping a workpiece can have a devastating effect on the overall cost of a manufacturing operation. In addition, a process operating at the outer boundaries of reliability cannot be run untended or semi-tended, eliminating a potential source of labour savings.

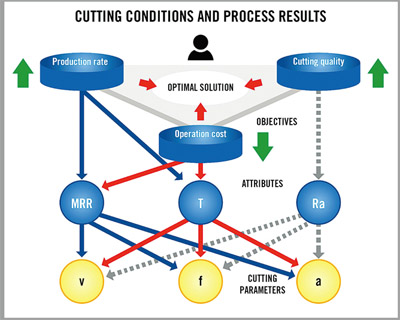

Raising cutting speeds also has direct effects on tool life. Speeds that are too high accelerate tool wear to the point that frequent tool changes become necessary. Because tools wear out faster, more tools are required to finish the same number of parts. Theoretical gains in manufacturing costs and productivity rates are reduced by added tooling costs and costs for machine tool downtimes.

Machine downtime costs

Higher speeds increase cutting tool costs but also initially drive down machine tool costs. Because the machine tool is producing more parts per period of time, more revenue can be applied against the machine’s fixed costs. However, as speeds rise beyond a certain point, machine tool costs begin to increase again. Tool life becomes so short that the decrease of the machine tool cost has a smaller effect than the fast increasing costs of tooling and downtime for tool changes. In addition, extremely high cutting speeds and very aggressive machining parameters in some cases can add to machine tool costs for maintenance and even result in downtime caused by unanticipated machine failures.

Optimal parameters

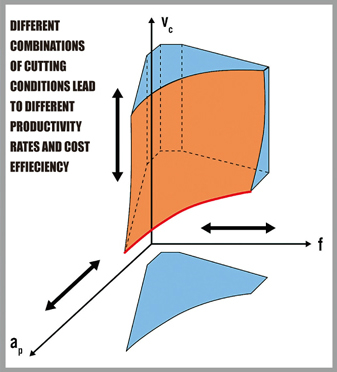

Application of higher cutting speeds can increase production rates, but somewhat higher tooling and machine tool costs may occur as well. Conversely, lower cutting speeds reduce tooling and machine tool costs but productivity generally falls.

A balanced approach involves reduced cutting speeds matched with proportional increases in feed rate and depth of cut. Utilising the largest depth of cut possible reduces the number of cutting passes required and thereby reduces machining time. Feed rate should be maximised as well, although workpiece quality and surface finish requirements can be affected by feed rates that are excessive. In some cases, increases in feed rate and depth of cut at the same or lower cutting speeds can raise the metal removal rate of an operation to that achieved by higher cutting speeds alone.

When a stable and reliable combination of feed rate and depth of cut has been reached, cutting speeds can be used for final calibration of the operation. The target is a higher cutting speed that reduces machine tool costs (per produced workpiece) but does not excessively raise cutting tool costs (per produced workpiece) via accelerated tool wear.

A model of efficiency

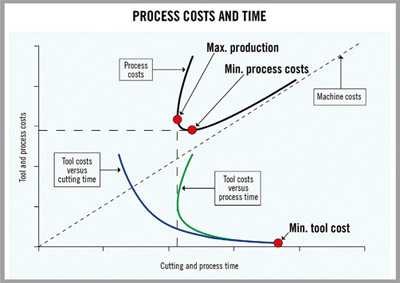

At the beginning of the 20th century, American mechanical engineer F.W. Taylor developed a model for determination of tool life. The model shows that for a given combination of depth of cut and feed there is a certain window for cutting speeds where tool deterioration is safe, predictable and controllable. When working in that window, it is possible to quantify the relation between cutting speed, tool wear and tool life. The model brings together cost efficiency and productivity and provides a clear picture of what to aim for when defining the optimum cutting speed for an operation.

At lower cutting speeds, the sum of cutting tool and machine tool costs produces maximum economy, at some cost to productivity. On the other hand, higher speeds provide maximum productivity, but economy suffers. Between the most economical cutting speed and the speed that maximises productivity is the High-Efficiency (HE) cutting speed.

As an aside, economical and technological issues sometimes coincide. For example, the toughness and poor thermal conductivity of titanium dictate that it be machined at lower cutting speeds, while lower cutting speeds in general result in lower machining costs. In this case, workpiece characteristics on their own lead to the adoption of machining parameters that provide a balance of productivity and economy.

Process stability is crucial

The key to maintaining productivity and part quality and avoiding scrap is establishing a stable machining process. A pragmatic definition of global production economics is “Assuring maximum security in, and predictability of the process, while maintaining highest productivity and lowest manufacturing costs”.

Establishing a stable process includes creation of an optimum production environment. In addition to choosing the tool material, coating and geometry best suited to the workpiece and operations at hand, consideration must be given to optimising the machining CAM program, tool holding systems, and coolant application. Workhandling automation such as pallet or robotic part load/unload systems should be part of the process integration as well, because handling of raw and finished part stock can consume significant amounts of machine downtime.

Additional issues

Beyond the long-established goals of productivity and economy, the manufacturing industry is putting increasing emphasis on relatively new concerns such as environmental issues. A balanced approach to production economics can help resolve those issues as well. At lower cutting speeds, less energy is required to remove material from the workpiece, and reductions in depth of cut accompanied by increases in feed rate provide further reduction in energy consumption. Lower cutting speeds increase tool life, reducing the consumption of tooling and the need to dispose of or recycle it. The reduced generation of heat resulting from application of lower cutting speeds can enable use of minimal or zero-coolant arrangements.

Neo Cloudfoam Pure

iConnectHub

iConnectHub

Login/Register

Login/Register Supplier Login

Supplier Login